Freud’s Psychology and Consumer Behaviour

The Unconscious Consumer in Marketing

Marketing is often seen as the art and science of influencing consumer decisions – and many of those decisions are not as rational as they appear. Over a century ago, Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theories posited that people are largely driven by unconscious desires and hidden motivations. Today, modern research seems to agree: studies indicate that up to 95% of purchasing decisions occur in the subconscious mind.

This suggests that;

“consumers often have no idea why they buy things”

…as marketing guru Ernest Dichter once observed.

Freud’s concepts – the unconscious mind, the id–ego–superego structure of personality, defence mechanisms, and instinctual drives; offer a framework for understanding these hidden influences on consumer behaviour.

This article explores how Freudian psychology has been applied in marketing, from the early days of advertising to contemporary branding strategies. We examine how unconscious emotions and desires shape consumer behaviour, highlight real-world examples (including famous campaigns influenced by Freud’s ideas), and discuss the strengths and limitations of using Freudian theory in marketing practice.

The Marketing Made Clear Podcast

Check out the Marketing Made Clear Podcast on all good streaming platforms including Spotify:

Freud’s Key Concepts and Consumer Behaviour

The Unconscious Mind in Purchasing

Freud revolutionised psychology with the idea that much of human behaviour stems from unconscious processes.

In the context of consumer behaviour, this implies that people’s buying decisions are often driven by desires and fears they are not consciously aware of. Modern marketers recognise that “consumer spending is largely shaped by unconscious and emotional urges,” and what consumers say they want may contradict what they actually buy. For example, a shopper might consciously seek a “practical” car but be unconsciously swayed by a flashy sports model that boosts their self-image. Freudian motivation theory posits that hidden psychological forces – childhood associations, repressed wishes, fantasies – can be triggered by products or ads to influence choices.

A classic illustration is the way marketers link products to unconscious needs: selling window blinds not just as decor but as a shield against the unconscious fear of being seen (privacy/anxiety). In short, consumers are not fully rational actors; as Freud asserted long ago, people are often “governed by irrational, unconscious urges” when making purchasing decisions.

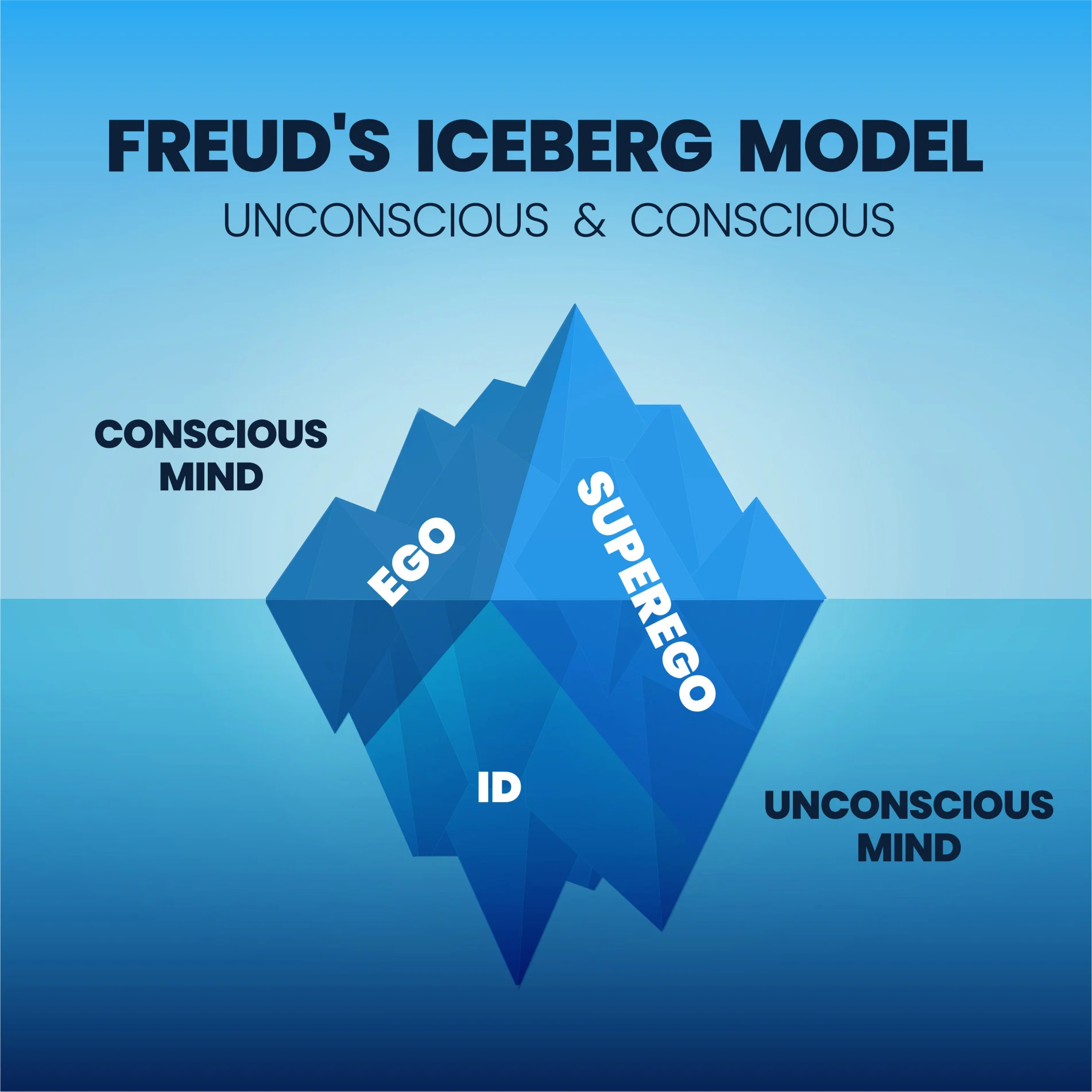

Id, Ego and Superego – The Consumer’s Psyche

Freud’s structural model of the psyche divides it into three interacting parts – the id, ego, and superego – which can be used as a lens to understand consumer impulses.

The ID

The id represents our primitive drives for pleasure and instant gratification. It is entirely unconscious and demands things that feel good – rich foods, comfort, sex, power – regardless of consequences.

In consumer terms, the id is the part of you that wants to splurge on a decadent chocolate cake or a luxury sports car purely for the thrill or indulgence.

Marketers often appeal to the id by emphasising pleasure, excitement, or sex appeal in advertising (hence the old saying “sex sells”).

The Superego

The superego, by contrast, internalises society’s morals and ideals – it is the voice of conscience and aspiration. In consumer behaviour, the superego might drive someone to buy products that reflect their ideal self or values: for example, choosing an eco-friendly brand to feel responsible, or a high-end watch to project success and gain social approval.

The Ego

The ego is the conscious self that mediates between the id’s desires, the superego’s restraints, and reality. It tries to make rational choices that satisfy both inner urges and societal expectations. In marketing, the ego comes into play when consumers weigh options and seek justifications for their choices. Notably, the ego often engages in rationalisation – finding logical reasons to justify an impulse buy that was emotionally driven. (Indeed, behavioral research confirms that people “buy on emotion and justify with logic,” aligning with the Freudian view that the ego rationalises the id’s wishes.) Marketers cater to this by providing plausible justifications in their messaging – for instance, a sports car ad might highlight safety features (to appease the ego/superego) even as the car’s design clearly appeals to primal desires for thrill and status.

Freudian Defence Mechanisms in Consumer Life

Freud’s theory of personality included defence mechanisms – unconscious mental strategies to cope with anxiety or internal conflict. Several of these mechanisms manifest in consumer behaviour and are leveraged (or inadvertently triggered) by marketing. One common example is sublimation, where people redirect unacceptable impulses into socially approved activities.

Shopping can serve as a sublimation outlet: someone stressed or angry might unconsciously “work off” those feelings by indulging in retail therapy (buying treats for themselves), a behaviour that is socially acceptable compared to, say, getting into a fight. Psychologists note that “sublimation is what leads to stress eating and stress shopping” – it relieves tension in the short term, though it “may be socially acceptable [and harmless to others], it can hurt your wallet in the long run”. Advertisers tap into this by positioning products as rewards or mood enhancers (think of slogans like “You deserve it” after a hard day).

Another relevant mechanism is projection, where one ascribes their own feelings to others. In marketing, projection might occur when a consumer attributes their purchase preference to a product’s supposed qualities (“*I bought this SUV because it’s the safest on the market,” when in fact it makes them feel secure and powerful). Rationalisation, as mentioned, is also key – consumers often concoct rational reasons for irrational purchases, and savvy marketing provides those reasons (e.g. a pricey fashion item is “an investment in quality”).

Denial can appear when consumers ignore negative information about a product they desire (such as health risks of cigarettes in the era of tobacco advertising), and regression might explain nostalgic purchases that harken back to one’s childhood comforts.

Marketers, knowingly or not, play to these defence mechanisms.

For instance, campaigns for comfort foods during tough times effectively encourage a mild regression to the carefree feelings of youth. By understanding these subconscious coping strategies, marketers can better predict and influence how consumers respond to messaging – or at least avoid triggering defences that reject a sales pitch.

Emotional and Instinctual Drives

At the heart of Freudian theory is the idea that fundamental drives – notably sex and survival – underlie much of human action. Freud’s concept of the libido (sexual energy) and the pleasure principle (seeking pleasure, avoiding pain) is highly relevant to consumer motivation. Ernest Dichter, a psychologist and protégé of Freud who became a pioneer of consumer research, famously argued that “pleasure, and specifically sex, was at the core of consumer behaviour.”

He showed through studies that even everyday products carried symbolic sexual meaning for consumers. For example, Dichter found that the sensual enjoyment of eating and smoking could be marketed as guilt-free indulgence by subtle messaging. He advised brands to tap into the eros (life/sexual drive) of consumers – selling “the dream” associated with a product rather than the product itself. One of Dichter’s key insights, echoing Freud, was that “man…is more strongly motivated by the pleasure principle than by the reality principle,” meaning emotional gratification often wins over practical utility.

Advertisers took this to heart by creating ads that promise excitement, romance, or adventure.Think of fragrance commercials filled with erotic imagery or sports car ads likening the car to an object of desire – these appeal straight to the id.

Power and Status

Another drive, less explicit in Freud but equally powerful, is the drive for power and status (one might link this to Freud’s thanatos or aggression drive, channeled socially). Many consumer choices, from luxury goods to upscale gyms, are driven by an unconscious desire for dominance, prestige, or envy from others. Marketing campaigns often subtly play on these instincts – for instance, an advertisement might imply that owning a certain smartphone makes you part of an elite, forward-thinking group (appealing to both status and belonging needs).

By aligning products with deep emotional drives like lust, fear, or ambition, marketers trigger responses that a purely rational pitch could never achieve. It’s no coincidence that some of the most successful advertising slogans and campaigns in history bypass straightforward product details and instead evoke feelings – from Coca-Cola’s focus on “happiness” to Nike’s “Just Do It” call to personal triumph.

Freudian Theory in Marketing Practice

Freud’s influence on marketing began in the early 20th century with the realization that advertising could do more than inform – it could persuade by appealing to unconscious desires. Freud’s own nephew, Edward Bernays, was instrumental in applying psychoanalytic ideas to public relations and advertising. Bernays understood that

“people act on information, but they act much more strongly if you connect with them on a deep, unconscious level.”

Building on his uncle’s theories, “Bernays… discovered this,” becoming one of America’s first marketing superstars by crafting campaigns that appealed to subconscious emotions rather than logic.

An often-cited example is Bernays’ 1929 “Torches of Freedom” campaign, which successfully encouraged women to smoke in public by equating cigarettes with female empowerment. At the time, it was socially taboo for women to smoke. Bernays orchestrated a stunt during New York’s Easter Parade in which fashionable young women lit up Lucky Strike cigarettes, proudly dubbing them “torches of freedom.” One participant, Bertha Hunt, declared to the press,

“I hope that we have started something and that these torches of freedom… will smash the discriminatory taboo on cigarettes for women.”

This was…

“people’s good intentions being exploited for profit,”

…as one observer drily noted on reddit.com – an early example of how Freud’s ideas about human urges could be used to manipulate consumer behaviour on a grand scale.

Advertising and the Unconscious

Bernays’ work signalled a shift from straightforward, fact-based advertising to a more psychological approach. Instead of just listing product features, ads began to imply that buying certain products would satisfy deep-seated desires – for security, status, sex appeal, or social acceptance.

By the 1950s, Ernest Dichter had turned ad agencies into “psychology labs” where he conducted in-depth interviews and focus groups (what he called “motivation research”) to probe consumers’ hidden feelings about products. His findings led to ads that addressed the unconscious. For example, car advertisements started to emphasise how a car made you feel (powerful, attractive, free) rather than just its engineering.

Dichter unabashedly “brought sex into advertising,” discovering that products as mundane as soap or as common as cake mix could have erotic or symbolic connotations for consumers.

One famous anecdote attributed to Dichter is the case of Betty Crocker cake mix in the 1950s: sales improved after the recipe was tweaked to require adding an egg. His interpretation was that the simple act of adding a fresh egg allowed housewives to unconsciously feel more invested in the cake (symbolically adding a bit of themselves, easing their guilt about using a mix).

Whether apocryphal or not, the story illustrates how a minor product change, informed by psychological insight, addressed an unconscious conflict (the homemaker’s superego need to feel she was baking “properly”) and thus boosted sales. In general, Freud-informed advertisers excelled at finding symbols that resonated with consumers’ psyches.

A convertible car might be marketed as an expression of virility and freedom (id desires), whereas a home security system ad might subtly play on the fear of chaos (thanatos drive) and promise peace of mind. Even the imagery in ads often contains unconscious cues – a perfume advertisement might place the product in a setting evoking sensual pleasure (dark red velvets, night-time city lights) to stir unconscious lust or romance. As one marketing article showed, advertisers learned to use Freud’s insight that humans are “impressionable, emotional and irrational”, by crafting messages that spoke to feelings first and foremost.

Emotional Branding and Aspirational Marketing

Freudian theory has left a lasting mark on branding – the practice of endowing products with personalities and emotional narratives. Emotional branding means forging a strong affective bond between brand and consumer, often by appealing to the consumer’s sense of identity or aspirations. This has parallels with Freud’s idea of identification, where an individual aligns themselves with another person or image.

For instance, lifestyle brands like Apple or Nike don’t just sell electronics or shoes; they sell an ideal self-concept. Apple’s marketing for years tapped into a desire to be creative, innovative, and “think different” (attracting consumers who unconsciously see Apple as a symbol of the creative rebel they’d like to be). Nike’s campaigns feature hero-athletes and slogans that speak to inner drive, inspiring consumers to associate the brand with personal achievement and courage.

In Freudian terms, these are appeals to the ego ideal (the part of the superego representing who we wish to become).

Aspirational marketing in general often shows idealised lifestyles – beautiful models, luxury settings, happy families – which trigger consumers’ unconscious longing to live that life. Buying the product is positioned as a step toward that dream. A luxury watch ad, for example, might hardly mention the watch’s technical qualities; instead it depicts a successful, admired man in an elegant setting, subtly suggesting that the watch is part of what makes him enviable. Consumers with a strong need for status or approval (often unconsciously driven by childhood experiences of self-worth) respond to these cues. They purchase not just a good, but a piece of an identity. This technique can be very powerful: by fulfilling not a functional need but an emotional one (esteem, belonging, attractiveness), brands gain extraordinarily loyal customers.

It’s no accident that some brand communities have near-fanatical followings – they are fulfilling psychological needs and drives that Freud spent his life analyzing. However, marketers must balance this by ensuring the ego has some rational hook to justify the emotional choice. Often, the brand storytelling provides that hook (e.g., “this car also has great safety ratings,” or “this skincare product is scientifically advanced”), allowing the consumer’s conscious mind to feel sensible while the unconscious is sold on the dream.

Subliminal Messaging – Myth or Reality?

No discussion of Freud in marketing is complete without mentioning subliminal advertising – the attempt to send messages below the threshold of conscious awareness. This idea stems directly from the Freudian assumption that the unconscious mind can perceive and store stimuli that the conscious mind misses.

In the 1950s, the public became fascinated and terrified by the prospect of subconscious manipulation through ads. The spark was an infamous 1957 experiment by marketing researcher James Vicary, who claimed that flashing the phrases “DRINK COCA-COLA” and “EAT POPCORN” for a fraction of a second during a film caused moviegoers to buy more of those snacks. According to reports at the time, the hidden commands (visible on screen for only 1/3000th of a second) led to an 18% jump in Coke sales and 58% jump in popcorn sales. The idea that advertisers could literally control the unconscious mind caused an uproar. While Vicary’s results later turned out to be dubious or even a hoax, the incident cemented the notion of subliminal advertising in popular culture. From then on, people began to suspect ads of containing hidden sexual images or secret words meant to influence behaviour. Advertisers, intrigued by the concept, sometimes did embed subtle imagery. In the 1970s, for example, a rumour (and urban legend) held that liquor ads hid the word “SEX” in ice cubes or clouds in the background – a supposed ploy to arouse viewers’ libidos just enough to make them pay attention.

While the most lurid claims of subliminal ads are not supported by solid evidence, the underlying principle is sound: unconscious perception exists, and subtle cues can influence us. Modern research has shown that people can be primed by stimuli they don’t consciously recall – for instance, flashing quick positive or negative words can affect mood or behaviour in experiments.

Marketers use this knowledge in more measured ways now, such as product placement in films (where seeing a brand incidentally might build familiarity without explicit persuasion) or the use of faint background imagery and colour psychology.

Even without true “hidden messages,” advertisers certainly aim to bypass rational filters. A visually arresting logo, a catchy jingle, or a brief appearance of a product in a favourite TV show all work at a level below active scrutiny – the goal is to embed the brand in your memory or associate it with positive feelings without you stopping to think “why do I like this?”. In that sense, the spirit of subliminal influence – appealing to the unconscious – very much lives on, even if the original sci-fi idea of brainwashing consumers with single-frame flashes has been discredited. Freud’s legacy here is the emphasis on the implicit, the notion that what is not said (or not consciously noticed) can be as powerful as what is overt.

Case Examples in Modern Marketing

Freudian concepts continue to surface in contemporary campaigns and strategies. Consider emotional appeals in advertising: a 2020s Super Bowl commercial might have no logical connection to the product, yet by making viewers laugh or feel sentimental, it creates positive emotions that become linked to the brand unconsciously.

Insurance companies, oddly enough, often use humour or cute mascots – this could be seen as disarming our defence mechanism of denial about unpleasant subjects like accidents, making us more receptive to the message.

The use of sexuality in advertising remains pervasive – from colognes to car ads – directly appealing to the id. A brand like Calvin Klein built its image on risqué, voyeuristic ads that implicitly told consumers that wearing their fashion would make them sexually desirable (or at least as confident as the models in the ads).

On the other hand, aspirational marketing is evident on platforms like Instagram, where influencers portray an ideal lifestyle; companies then advertise products as little pieces of that lifestyle. Buying a certain protein shake or suitcase is subtly presented as a way to attain the fit, globe-trotting ideal we see on social media – a clear play on our unconscious aspirations and even our insecurities.

Another modern twist is neuromarketing, where companies use brain-scanning technology and psychological testing to see how consumers’ unconscious minds respond to stimuli. This high-tech approach is essentially Freudian in spirit: it assumes much of what drives purchase decisions is non-conscious and seeks to uncover those hidden responses (though with fMRI machines rather than a psychoanalyst’s couch). For example, a company might test which version of an ad elicits more emotional brain activity, betting that will translate to better sales.

Product design and packaging also employ Freudian insights. Designers talk about “sensory marketing” – using touch, color, sound and scent to create an emotional ambiance around a product. A well-known example is how fast-food chains use the color red and enticing food imagery to stimulate appetite (red can spur hunger and excitement, an id response), whereas luxury boutiques use subdued lighting and soft textures to slow customers down and make them feel comforted (almost womb-like, one could argue). These practices show the enduring idea that to win consumers’ hearts (and wallets), marketing must reach beyond cold facts to the realm of emotion and unconscious motivation.

Strengths and Limitations of Freudian Marketing

Strengths

Freudian theory’s greatest strength in marketing is its explanatory power for the irrational aspects of consumer behaviour. It provides a vocabulary and framework for why consumers sometimes behave against their own stated interests – why they might prefer a pricy, inferior product that “feels right” over a cheaper, superior alternative. By acknowledging unconscious motives, marketers can craft strategies that resonate on a deeper level.

Campaigns inspired by psychoanalytic insight have yielded legendary results (as we saw with Bernays’ smoking campaign or Dichter’s work boosting sales for numerous brands). Freud’s concepts encouraged marketers to explore symbolism, storytelling, and emotion, making advertising far more effective and engaging than a simple listing of features. This approach led to the development of focus groups, projective tests, and other qualitative research methods in marketing – tools that are still in use. Even today, when a car company conducts focus groups asking people to imagine the car as an animal or describe its personality, they are using Freudian projective techniques to get at feelings people can’t directly articulate. The benefit is uncovering insights that traditional surveys miss. Furthermore, many of Freud’s general ideas have been vindicated by modern psychology: people are often driven by impulses outside conscious awareness, and emotion does heavily influence decision-making.

Thus, marketing that leverages emotion (a very Freudian notion) tends to outperform marketing that appeals only to reason. In an age where consumers face information overload, tapping into the unconscious through brand images, emotional storytelling, and aspirational messaging can cut through the clutter – the ad speaks to the consumer’s core needs and desires, not just their intellect.

In short, Freud’s legacy in marketing is the insight that selling to the mind means selling to the heart (and the hidden mind), not just the head. This remains a cornerstone of advertising strategy.

Limitations

Despite its contributions, a Freudian approach to marketing has significant limitations.

First, Freud’s theories are not scientific in the strict sense – many of his ideas are hard to test or measure. This means that basing a marketing strategy purely on Freudian theory can lead to unfounded assumptions. Indeed, one reason classic psychoanalysis fell out of favour in psychology is that “Freud’s theoretical model of the mind…has been challenged and refuted by a wide range of evidence.” and his ideas “gained little empirical support.”

In marketing, this translates to the risk of seeing meaning where there is none (for example, over-interpreting consumers’ behaviours as sexual or Oedipal when there may be more straightforward explanations). A classic critique came from the philosopher Karl Popper, who called psychoanalysis a pseudo-science because it’s so flexible that it can explain anything retroactively but predict nothing definitively.

Marketers must be wary of this trap – psychoanalytic interpretations can become so subjective that they lose practical value. Another limitation is that Freudian theory overemphasises instinctual drives (especially sex) and largely ignores other factors like culture, social context, and cognitive processes. Modern consumer behaviour research points to many influences beyond unconscious libido or childhood trauma – for instance, peer influence, conscious goal-setting, heuristics and biases in decision-making, and so on.

Relying solely on Freud could mean overlooking these elements. Moreover, not all consumers respond uniformly to Freudian appeals. Freud’s model was one-size-fits-all and rooted in a specific historical context (Victorian European society).

Today’s consumers are more diverse and also more aware of marketing tactics.

What worked in the 1950s might not work now; for example, subliminal tricks or overt sexualisation can backfire with a public that’s media-savvy and sometimes cynical about advertising. There are also ethical concerns. Using psychological manipulation – especially tactics designed to exploit unconscious weaknesses (like insecurities about body image or latent anxieties) – raises questions about consumer autonomy.

The “Torches of Freedom” case, in hindsight, was applauded for striking a blow for women’s liberation, but it was fundamentally a tobacco company ploy to get women addicted to cigarettes under the guise of feminism. Such manipulation can be seen as underhanded or even harmful (indeed, it led to more women smoking and suffering health consequences).

Lastly, a practical limitation: Freudian marketing can sometimes lead to overcomplicated messaging. Not every product needs a deep psychoanalytic backstory – sometimes consumers just want a simple, conscious reason to buy (e.g., it tastes good, it’s affordable). If a marketer is too enchanted by cryptic symbolism, they may miss the obvious appeal of their product.

In summary, Freud’s theories opened marketers’ eyes to the rich inner world of the consumer – a world of wishes, fears, and longings that is not immediately visible on the surface. This has undoubtedly made marketing more effective and advertising more artful. Yet, it is one lens among many. The best marketers often integrate Freud’s insights about emotion and the unconscious with data-driven approaches and other psychological models. They might use Freudian ideas to brainstorm creative angles (for example, “what unspoken desire could our branding fulfill?”), then test those ideas with research and metrics. After all, understanding consumers is both an art and a science. Freud supplied much of the art; modern marketing science can validate which of those artistic hunches truly resonate.

Conclusion

From Freud’s consulting room in 1900 to the branded content on our Instagram feeds today, the thread of psychoanalysis in marketing is unmistakable.

Freud taught the world that much of human behaviour lies below the surface – and marketers ran with that idea, learning to speak the language of the unconscious. We have seen how concepts like the id, ego, and superego map onto consumer motivations, how defence mechanisms and hidden drives explain quirks of buyer behaviour, and how campaigns from the mid-20th century to the present have leveraged those insights.

Using Freudian theory, advertisers have created messages that bypass our reason and touch our emotions, influencing us in ways we might not fully realise. This has led to some of marketing’s greatest triumphs, but also reminds us of the need for caution and ethics.

Consumers are not pawns to be brainwashed – trust and authenticity matter in the long run, and even the unconscious can become wary of manipulation if a brand oversteps.

The legacy of Freud in marketing is a double-edged sword: it gives us powerful tools to connect with consumers’ deepest selves, but it also demands a responsibility to use those tools wisely. In a world where consumers are more empowered and informed than ever, the most effective marketing will likely be that which harmonises Freud’s timeless insights about emotion and desire with a genuine respect for the consumer’s conscious values and choices. Marketers who achieve this balance – appealing to the heart and subconscious, while satisfying the mind – will continue to build brands that are not only purchased, but loved (often for reasons the consumer couldn’t begin to explain). Such is the enduring dance between Freud’s psychology and the marketplace: an exploration of why we buy, revealing as much about ourselves as it does about the products we consume.