Buyers in Conflict: The Role of Cognitive Dissonance in Marketing

From Pre-Purchase Anxiety to Post-Purchase Regret – and How Brands Can Respond

Cognitive dissonance is a foundational theory in psychology that describes the mental discomfort people experience when they hold conflicting beliefs, attitudes, or values. Leon Festinger’s seminal work A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957) introduced the idea that individuals are motivated to resolve such internal conflicts to restore consistency.

In the fields of marketing and consumer behaviour, this theory has far-reaching implications.

Consumers often find themselves “in two minds” about a purchase – for example, wanting a product but feeling it contradicts their budget or values. This deep dive article explores the theory of cognitive dissonance and examines how it influences consumer decision-making at every stage. We will discuss how dissonance can sway purchase decisions, how marketers leverage or mitigate dissonance in practice, and what strategies are used to reduce buyers’ post-purchase remorse. The aim is to provide marketing students and professionals with an accessible yet academically grounded analysis of cognitive dissonance in consumer behaviour, complete with real-world examples and references to key research.

The Marketing Made Clear Podcast

Check out the Marketing Made Clear Podcast on all good streaming platforms including Spotify:

Cognitive Dissonance – Theoretical Background

Cognitive dissonance theory explains how conflicting cognitions give rise to psychological tension and drive people to reduce that tension. Festinger proposed that humans have an inner need to ensure their beliefs and behaviors are consistent. When a person holds two relevant cognitions that conflict, for example:

- “I value health” and

- “I smoke cigarettes”

…the clash produces an uncomfortable state known as dissonance. This dissonance is experienced as stress or anxiety, and the individual becomes motivated to resolve it.

According to Festinger, the greater the magnitude of the inconsistency, the greater the pressure to reduce it. People may reduce dissonance by changing one of the conflicting beliefs, adding new beliefs, or changing their behavior. For instance, a smoker who values health might quit smoking, rationalize that “occasional smoking isn’t that bad,” or seek out information that downplays smoking’s risks – all are methods to alleviate dissonance.

Cognitive dissonance is fundamentally about this drive for internal consistency.

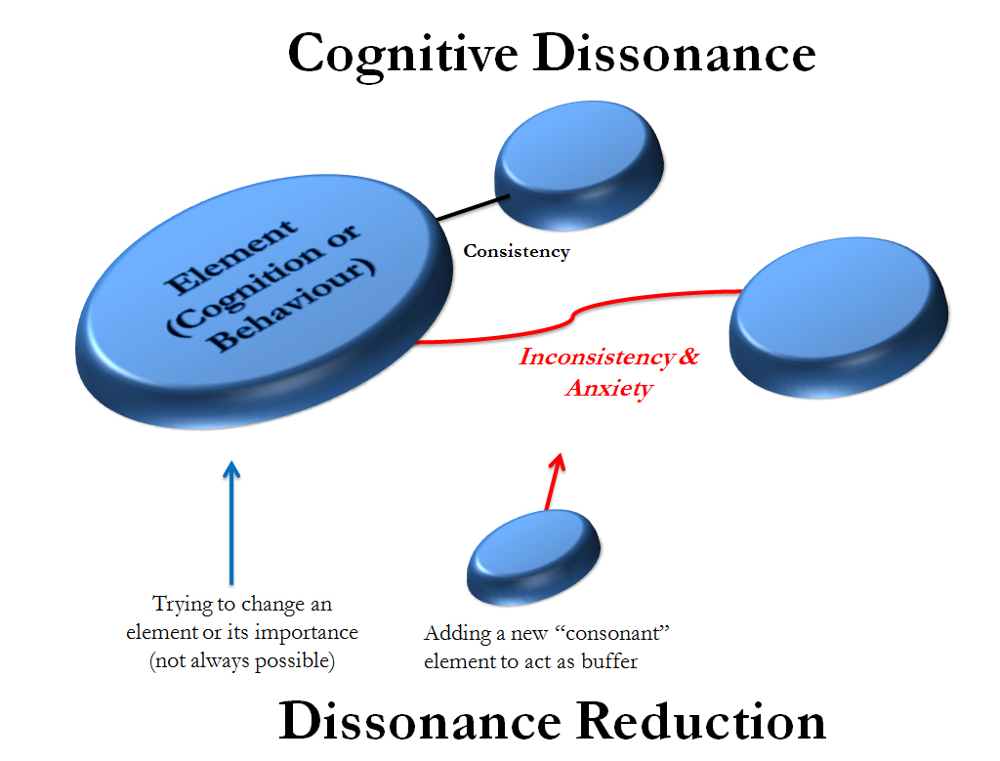

To the right, you can see a simplified diagram of cognitive dissonance, where an inconsistency between elements (beliefs or behaviours) causes anxiety, prompting dissonance reduction by either changing elements or adding new “consonant” information. In Festinger’s classic observation of a doomsday cult, members faced disconfirmation of their beliefs when the world did not end as predicted.

Rather than abandon their beliefs, many members resolved the dissonance by altering their cognition – for example, convincing themselves their faith had averted the disaster. This demonstrated the lengths to which people will go to reduce incongruent cognitions.

Over the decades, researchers like Elliot Aronson and others expanded on Festinger’s work, showing that dissonance is strongest when the conflict involves one’s self-concept or when the individual feels personally responsible for their actions. The theory remains one of the most influential in social psychology, explaining phenomena from attitude change to decision rationalisation. In essence, whenever consumers feel the sting of contradiction between “what I think” and “what I do,” cognitive dissonance is at play.

Cognitive Dissonance in Consumer Behaviour

Cognitive dissonance heavily influences consumer attitudes and behaviours. In marketing contexts, it often manifests as purchase anxiety or buyer’s remorse. For example, a consumer may covet an expensive new smartphone but simultaneously believe that spending large sums on a phone is irresponsible. This conflict creates dissonance and an uncomfortable tension during the decision process. If unresolved, the consumer might forgo the purchase to eliminate the tension, or if they proceed to buy, they may later feel regret. Dissonance in this sense can deter a purchase or diminish satisfaction after the fact. Marketers should be aware that a customer who feels conflicted or guilty about a decision is less likely to become a repeat buyer.

A classic definition of post-purchase cognitive dissonance is the doubt or anxiety felt after making a difficult choice – commonly known as buyer’s remorse. Once a purchase is made, consumers often justify their decision to alleviate dissonance. They seek reassurance that they made the right choice.

Research in the field of psychology notes that after choosing an item, people tend to amplify the merits of their choice and devalue the alternatives they didn’t choose. In other words, the buyer convinces themselves “I made the best choice” to resolve lingering doubts. They may selectively seek out information that confirms their decision and avoid information that undermines it. For instance, a new car owner might read positive reviews about the model they bought and ignore any negative press.

This selective exposure is a dissonance-reduction tactic: consumers prefer information that aligns with their prior choice or opinion and avoid messages that would increase their unease. If the product encounters problems (say the car has a mechanical issue), the consumer might experience renewed dissonance (“I thought this was a good car, but now it seems flawed”). They might cope by downplaying the issue (“It’s just a minor glitch, overall it’s great”) or by seeking validation from others (“But every car in this class has some problems”) to preserve a positive view of their purchase.

Not all dissonance occurs after buying; pre-purchase dissonance can also shape consumer behavior. While deciding between alternatives, a consumer can feel torn if each option has attractive features. This choice anxiety is essentially cognitive dissonance before a decision is made. For example, someone shopping for a laptop might find one model with a better screen but another with better battery life – neither is a clear winner, and holding the competing preferences causes internal conflict. Consumers deal with this by using simplifying strategies. They might deliberately focus on one or two key attributes (e.g. “battery life matters most”) to justify a choice, or rely on a heuristic like brand loyalty or price to break the tie.

By narrowing the criteria, they reduce the cognitive dissonance that comes from having to sacrifice some benefits. In summary, dissonance can influence multiple points in consumer behaviour: it can

- Discourage purchases (if the conflict isn’t resolved).

- Motivate extensive information search or justification to enable a purchase

- Lead to attitude changes post-purchase to align with the consumer’s actions.

Marketers should strive to understand these patterns so they can either provoke a bit of dissonance to nudge behaviour (e.g. highlight a gap that the product fills) or, more often, reassure consumers to keep them satisfied.

Cognitive Dissonance Across the Consumer Decision-Making Process

Need Recognition

The consumer decision process often begins when a person recognises an unmet need or problem.

Cognitive dissonance can actually trigger need recognition by highlighting a discrepancy between the consumer’s current state and desired state. Marketers sometimes deliberately invoke dissonance at this stage: advertisements point out an inconsistency in the consumer’s life to create a sense of need. For instance, an ad might suggest, “Your life isn’t complete without Product X,” thereby suggesting that the consumer’s self-image or happiness is at odds with their reality of not owning the product.

A vivid example is a shampoo commercial described by marketing researchers: it shows a model with gorgeous, healthy hair and implies the viewer could be equally confident and beautiful if they use that shampoo. The viewer experiences a twinge of dissonance because they want to see themselves as attractive and vibrant, yet they aren’t using the advertised product.

As Dr. Matt Johnson notes,

“many ads are set up to make an explicit claim that you’re only cool or worthy if you own this product or service”.

This messaging creates a psychological tension that can only be resolved by either rejecting the ad’s premise or by deciding that the product is needed. In many cases, consumers resolve the dissonance by accepting the message and forming an intention to buy the product. In short, by leveraging cognitive dissonance in advertising, marketers can prod consumers into recognizing a new need – the first step in the buying process.

Information Search

Once a need is recognised, consumers gather information and explore options. Cognitive dissonance plays a role here by influencing how consumers seek and process information. A consumer who is already leaning toward a certain option may experience dissonance when encountering information that contradicts their inclination.

To minimise this, people often engage in selective information search: they gravitate toward sources that confirm what they want to believe and avoid those that don’t. If someone is excited about buying a particular smartphone, they might avidly read positive user reviews and skip over articles that criticise the phone’s faults. This behaviour is a dissonance reduction strategy – it shields the consumer from new doubts while they are in the decision process. Conversely, if a consumer feels uneasy about all options (say every choice has a downside causing internal conflict), they might prolong their search for information, hoping to discover something that clearly justifies one choice and resolves their indecision.

Extensive comparison-shopping or consulting many sources can be a sign of pre-purchase dissonance at work, as the person is essentially seeking consonant information to tip the scales. Marketers should be aware of this tendency. It means that consumers predisposed to their brand will seek reassurance (which the marketer can provide via readily available positive information, testimonials, etc.), whereas consumers not favouring their brand may avoid their messages entirely. Ensuring that reassuring information (like verified positive reviews, expert endorsements, or detailed FAQs) is easily accessible to interested customers can help ease information-stage dissonance. On the other hand, too much negative information readily visible can exacerbate conflict and scare the buyer away. Ultimately, during information search consumers are balancing the desire to make an informed choice with the desire to stay comfortable – and cognitive dissonance is the force that makes truly impartial evaluation emotionally difficult.

Evaluation of Alternatives

In this stage, the consumer weighs the pros and cons of different products or brands. The act of evaluation can heighten cognitive dissonance, especially when alternatives are closely matched. If each choice has unique advantages that the others lack, the consumer experiences an internal conflict: by choosing one, they must give up something offered by another. This is often described as the “spread of alternatives” effect in decision theory – whichever option is chosen, the attributes of the forgone option will linger in the consumer’s mind and potentially cause second-guessing. Pre-purchase dissonance is common here. The person might feel anxious thinking “Option A has a better design, but Option B is cheaper… whichever I choose, am I doing the right thing?”. One outcome of this tension is that consumers may simplify their decision-making criteria to reduce the mental conflict.

Research suggests that under dissonance, consumers adopt decision heuristics – for example, deciding that brand reputation or price is the deciding factor – rather than agonising over every attribute. By doing so, they bring their attitudes in line to favour one alternative strongly and diminish their liking for the others, which reduces the dissonance that comes from having equally attractive options.

Another outcome is that consumers might seek social proof or validation as a tiebreaker. If internally conflicted, a shopper may ask friends for opinions (“Which would you pick?”) or see which option is rated highest by other customers. A highly rated or bestseller product provides an external justification for their choice, easing the worry that they’re picking wrongly. If dissonance remains high and unresolved, the consumer may delay the decision or avoid it entirely. Marketers should have an interest in helping consumers confidently evaluate alternatives. Providing comparison charts, emphasising unique selling points (to make one option clearly stand out), or offering trial periods (“try both, return one”) are ways to assist in this stage.

These tactics aim to reduce the evaluative dissonance by either resolving the approach-approach conflict (making one choice more obviously fitting) or assuring the consumer that choosing is not irrevocable.

Purchase Decision

The moment of decision – deciding to proceed with a purchase – can also involve cognitive dissonance.

By this point, the consumer has more-or-less decided on a solution, but they may still harbour last-minute doubts (“Is this really the right choice? Should I spend this much?”).

Marketers often attempt to reduce dissonance at the point of sale to prevent abandonment. For example, a salesperson might use reassuring language like “You won’t regret this – this product is our best in class and you’re getting a great deal” as the customer is about to buy. Such reassurance is not just flattery; it actively works to counter any contradictory thoughts in the buyer’s mind (“maybe this is too expensive…”) with affirmations (“it’s worth it, and I’m wise for buying it”).

Many buyers also create personal justifications at this stage to seal the deal, telling themselves things like “I deserve this,” or “It’s an investment.” Indeed, an iconic marketing strategy by L’Oréal in the 1970s tapped directly into this self-justification impulse: the slogan “Because you’re worth it” was used to alleviate the guilt some women felt about buying premium beauty products. At the moment of purchase, this message reminds the consumer that treating oneself is justified – effectively resolving the conflict between the desire for the luxury item and the frugal attitude that might discourage the splurge. By validating the purchase (“you’ve earned it, you merit this indulgence”), L’Oréal helped consumers finalize decisions without regret.

Purchase-phase dissonance can also be mitigated by risk-reduction policies right at checkout. For instance, an electronics retailer might prominently display a “30-day money-back guarantee” notice. Knowing they have an out if doubts persist makes consumers feel less internally conflicted when handing over their payment, because any dissonance that arises can be resolved later by returning the product. In summary, during the purchase decision, immediate assurances – whether in messaging, salesperson input, guarantees, or supportive slogans – play a critical role in quieting any last-minute cognitive dissonance and encouraging the consumer to follow through.

Post-Purchase Behaviour

After the purchase, the consumer enters the post-purchase stage, where they use the product and evaluate their decision. This is the classic arena for cognitive dissonance in consumer behaviour.

Post-purchase dissonance (buyer’s remorse) refers to the buyer’s feelings of doubt or anxiety after the transaction is done, especially for significant purchases that were hard to reverse. Almost every consumer is familiar with the nagging thought, “Did I make the right choice?” If the product doesn’t immediately live up to expectations or if the consumer encounters new information (like a friend mentioning a better alternative or a sudden price drop elsewhere), the dissonance can intensify. For example, after buying an expensive laptop, a customer might read about a newer model coming out soon and feel conflicted – they love the laptop but hate knowing something possibly better was around the corner.

According to the theory, because the purchase is already done (final and often not easily undone if beyond the return window), consumers will actively work to reduce post-purchase dissonance. They might seek positive opinions from others: “Have you seen my new laptop? It’s been fantastic so far,” hoping friends will agree and reinforce that it was a good buy.

They often also change their attitude about the item and alternatives – convincing themselves that the chosen product’s advantages are really important and its drawbacks are trivial, whereas any not-chosen options would have had hidden problems. In essence, the buyer “increases the perceived attractiveness of the chosen alternative and devalues the non-chosen item” as a way to justify the decision to themselves. This self-justification helps diminish regret.

On top of this, consumers may filter information post-purchase: they’ll pay attention to advertisements or reviews that praise their purchased brand and subconsciously tune out criticisms (a continuation of selective exposure). If the dissonance is too strong – say the product truly disappoints – the consumer may resolve it by reversing the decision (returning the item) or voicing complaints.

From a marketing perspective, the post-purchase period is crucial: a dissatisfied, dissonant customer can tarnish the brand through negative word-of-mouth or by never buying from the company again. Satisfied, consonant customers, on the other hand, become repeat buyers and brand advocates. Thus, companies invest in dissonance-reducing measures at this stage (discussed in the next section). Overall, cognitive dissonance is almost inevitable after important purchases – whether the product is excellent or not – simply because making a choice forces one to forego other options. The goal for marketers is to ensure any post-purchase dissonance is minimal and short-lived, keeping the consumer happy with their decision.

Marketing Implications and Strategies

Understanding cognitive dissonance allows marketers to design strategies either to leverage that tension to influence choices or to alleviate it to improve customer satisfaction.

We can broadly categorise these strategies into two approaches:

- Inducing dissonance – to motivate consumers to change behaviour or attitudes in the marketer’s favour

- Reducing dissonance – to comfort the consumer and reinforce their decision

Leveraging Cognitive Dissonance

Marketers sometimes intentionally invoke dissonance to prompt consumers toward a desired action. Advertising is rife with examples, as noted earlier in need recognition. By pointing out a gap between the consumer’s self-image and reality, ads create a dissonant feeling that buying the product can resolve. Beyond ads that create an aspirational gap, comparative marketing can also induce dissonance in consumers loyal to a competitor.

A classic tactic is a side-by-side comparison that highlights your brand’s strengths versus a rival’s weaknesses. If done convincingly, it causes customers of the rival brand to feel a pang of dissonance (“My current choice might not be best, based on this new info.”) – potentially nudging them to reconsider and switch. For example, a campaign might say, “Unlike Brand X, our product doesn’t have issue Y,” implicitly suggesting that anyone using Brand X has made a suboptimal choice. This approach must be used carefully; if the consumer’s attachment to the competitor is very strong, they may simply reject the message to protect their current belief.

Another realm where dissonance is used is social influence and cause marketing. In public relations, communicators present information that clashes with the audience’s prior behavior or ignorance, aiming to change attitudes. A real-world case was a PR campaign for natural ingredient tampons: many women didn’t realise their usual products contained potentially harmful materials, so the campaign educated them about this fact. Learning this created cognitive dissonance in health-conscious consumers (“I care about my health, yet I’m using a product with unhealthy components”) – which in turn motivated many to switch to the new, “safer” product to resolve the discomfort.

In sales tactics, the well-known “foot-in-the-door” and “low-ball” techniques also rely on consistency and avoiding dissonance: getting a consumer to agree to a small request often increases the likelihood they’ll agree to a larger one later, because to refuse would create dissonance with their earlier behaviour (they would feel inconsistent).

Overall, leveraging dissonance is about carefully creating or exposing a conflict that the consumer can solve in a way that benefits the marketer – whether that’s buying a product, switching brands, or adopting a favourable attitude.

However, marketers must avoid pushing too hard; if the induced dissonance is overwhelming or the resolution unclear, consumers may just tune out the message entirely to escape the discomfort.

Reducing Consumer Dissonance

On the other side, a major part of marketing strategy is devoted to dissonance reduction – reassuring customers and aligning their experience to prevent or mitigate that mental discomfort. Smart companies recognize that a customer’s relationship with a brand doesn’t end at the sale; post-purchase support and communication are key to fostering loyalty. One common strategy is offering generous return policies or guarantees. A money-back guarantee is essentially an insurance against cognitive dissonance: if you regret your purchase, you can undo it.

Knowing this upfront significantly cuts down post-purchase anxiety. For example, online retailer Zappos became famous for its 365-day free return policy on shoes. Customers who might be on the fence (“Will these shoes actually fit and suit me?”) feel reassured that they won’t be stuck with a bad decision – reducing pre-purchase dissonance and encouraging the purchase. After buying, the option to return means the customer can resolve any strong dissonance by sending the product back, which is far better (from the company’s perspective) than the customer stewing in regret and bad-mouthing the brand.

Another strategy is proactive reassurance messaging. Companies often follow up a purchase with emails or calls to congratulate the customer on their choice, provide tips for use, or highlight the product’s benefits. These messages serve to confirm the wisdom of the decision. For instance, a salesperson at a clothing boutique might say as you check out, “That suit looks great on you – you made an excellent choice, it’s one of our best fabrics.” Such comments, though casual, are deliberately reinforcing the consonant thoughts (“I look good in this, it was a good buy”) and damping the dissonant ones (“Did I spend too much on this suit?”).

Some automobile dealerships will call new car buyers a week or two after purchase to “see if everything is okay” – in part to address any emerging concerns and reassure the owner, thereby heading off buyer’s remorse. A crucial tool for reducing consumer dissonance is social proof and community building. Marketers know that people take comfort in making the same choice that many others have made (the reasoning: “if so many others chose this, it must have been right”).

By showcasing positive testimonials, reviews, or user stories, companies provide the buyer with external validation. Seeing a five-star rating and comments like “Worth every penny!” from other customers can reassure someone who just bought the product that their feelings of satisfaction are justified and widely shared.

In fact, informational advertising that features user testimonials or independent test results is explicitly a dissonance-fighting technique: it gives the consumer factual and social support for their decision. If a customer had any lingering doubts, such information can tip their internal dialogue toward the positive. For example, after purchasing a new appliance, a consumer might receive an email saying “95% of buyers are happy with their XYZ washing machine – here are some of their stories.” This not only reminds them of why the product is good, but also signals that regret would be unfounded since the vast majority have no regret.

Customer service and after-sales support further help to reduce dissonance by addressing problems swiftly. If a customer encounters an issue and the company resolves it (through warranty service, troubleshooting, etc.), the negative feelings are less likely to turn into full-blown dissonance about the entire purchase. In contrast, if the customer feels abandoned with a faulty product, they will almost certainly regret the purchase and experience dissonance (“I believed this was a quality brand, but now I’m left with junk – I made a mistake”). That dissonance can permanently sour their attitude toward the brand. Therefore, investing in responsive support and clear communication is an important strategy to keep customers feeling positive post-purchase.

Finally, many brands attempt to preempt consumer dissonance by aligning their products with the consumer’s values from the start. If a brand successfully creates a strong emotional connection or identity (for example, Apple’s branding encouraging users to think of themselves as creative, innovative people), consumers who buy those products incorporate the purchase into their self-concept.

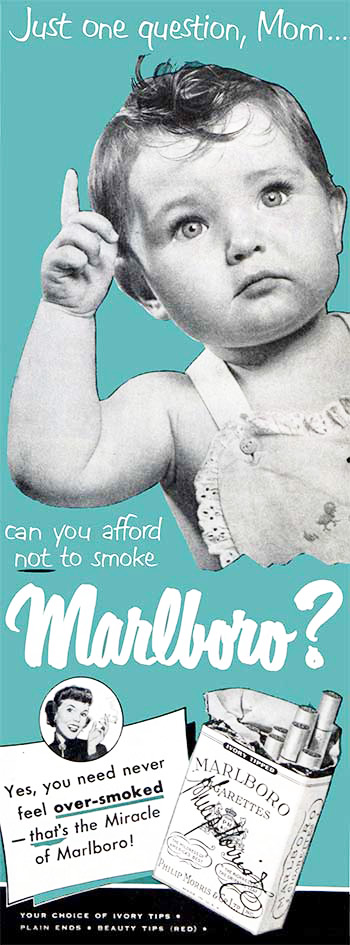

This makes them less likely to experience dissonance because the purchase feels inherently right for who they believe they are. In cases where dissonance still arises, companies sometimes respond with further messaging. For instance, cigarette companies in the mid-20th century faced growing health concerns among smokers – a classic cognitive dissonance scenario (“I enjoy smoking” vs. “Smoking might kill me”).

In response, tobacco ads in the 1950s leveraged authority figures and reassuring language to reduce smokers’ dissonance. One infamous Marlboro advertisement even featured a baby and the line, “Just one question, Mom… can you afford not to smoke Marlboro?”. By implying that a mother who cares for her child’s well-being would smoke filtered Marlboros (marketed as “milder” and hence safer), the ad attempted to neutralise the conflict a parent might feel about smoking. While this example is extreme and unacceptable by today’s standards, it illustrates the lengths marketers went to in order to keep consumers free of guilt and doubt. Modern marketers are more likely to use subtle methods – focusing on positive aspects, engaging customers in brand communities, and continually communicating value. The overarching goal is that when consumers reflect on their purchase journey, they feel a sense of harmony (consonance) rather than conflict. A customer whose expectations are met and whose beliefs and actions are aligned is more satisfied and more loyal.

Conclusion

Cognitive dissonance is a powerful psychological force shaping consumer behaviour. From the initial spark of realizing a need, through the weighing of options, to the final purchase and beyond, consumers strive to avoid the discomfort of inconsistent thoughts and choices. This paper has examined how that drive for consistency affects each stage of the decision-making process and how marketers can both leverage and alleviate dissonance.

Key contributors like Leon Festinger laid the groundwork by explaining why humans alter their attitudes to match their actions (or vice versa) when faced with inconsistency. In the marketplace, this means consumers will rationalize purchases, seek confirming information, and sometimes make surprising choices to resolve their internal conflicts. For marketers, the lesson is twofold.

- First, tactics that gently introduce a sense of discord (between the consumer’s current state and a desired state achievable with the product) can motivate action – effectively using cognitive dissonance as a marketing lever.

- Second, and most importantly, strategies must be in place to reduce post-purchase dissonance: reassuring communications, fair return policies, social proof of product quality, and excellent customer support all help ensure the customer’s experience remains positive and consistent with their expectations.

By addressing cognitive dissonance proactively, marketers can foster stronger customer relationships, turning one-time buyers into long-term loyal patrons. In accessible terms, when marketers understand the “mental wrestling match” that consumers go through, they can coach them toward a win-win outcome – a purchase that the consumer feels good about. In the end, aligning marketing practices with the psychology of cognitive dissonance leads not only to more effective persuasion but also to greater customer satisfaction.

Both the theory and the real-world examples show that helping consumers resolve their doubts is just smart business. A buyer at peace with their decision is more likely to become a repeat buyer, and nothing is more valuable in marketing than a customer who confidently believes they made the right choice.