The Rise and Fall of Napster

In the late 1990s, Napster burst onto the scene, fundamentally changing how people accessed and shared music. Founded in 1999 by Shawn Fanning, John Fanning, and Sean Parker, Napster was a peer-to-peer (P2P) file-sharing service that allowed users to share MP3 files. By 2000, Napster had exploded in popularity, boasting over 70 million users worldwide. This service essentially democratised access to music, making it possible to download virtually any song for free in minutes. However, it also triggered one of the most significant copyright battles in modern history, with the music industry waging a fierce campaign against it.

From my perspective, (which is of course a marketing perspective), Napster’s demise wasn’t just a legal defeat. It was a massive missed opportunity, both for Napster and the music industry. Napster had tapped into a profound consumer need: instant, affordable access to music, yet instead of capitalising on this, both Napster and the music industry spent the crucial years between 1999 and 2001 embroiled in legal battles.

This article explores how Napster and record companies could have shifted its focus toward creating a legitimate digital music marketplace, potentially transforming the industry years before Apple and Spotify capitalised on digital distribution.

Note:

This article features content from the Marketing Made Clear podcast. You can listen along to this episode on Spotify:

The Record Companies’ Reaction: Legal Battles and a Fear of Disruption

Napster’s meteoric rise didn’t sit well with record labels.

The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), representing the interests of major record labels, saw Napster as an existential threat to its business model. The industry, still rooted in physical media sales, primarily CDs, was largely unprepared for the digital revolution that Napster foreshadowed. While some individuals within the industry saw the potential in digital music, most executives considered Napster outright piracy.

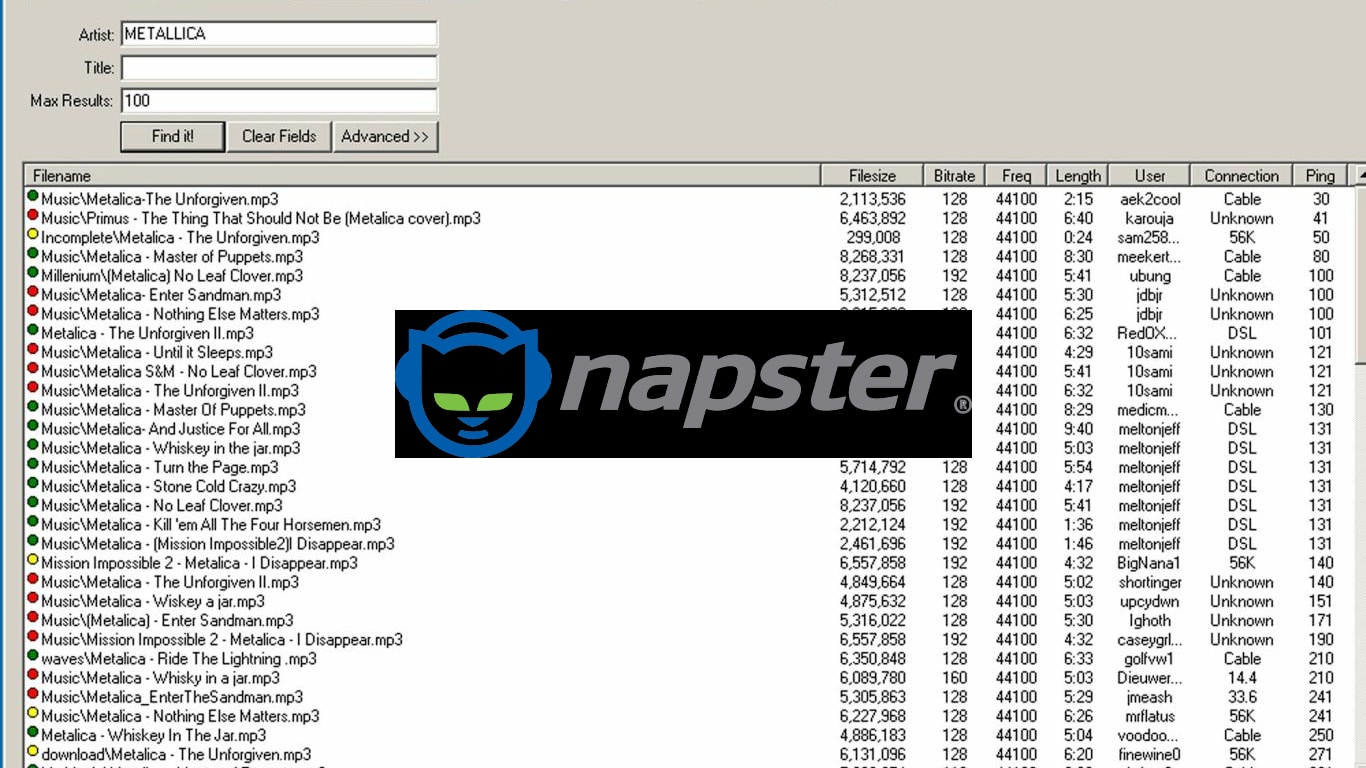

The RIAA, in conjunction with several artists like Metallica and Dr. Dre, launched high-profile lawsuits against Napster in late 1999 and 2000. Metallica, in particular, became the face of this battle when they filed a lawsuit after discovering that their song “I Disappear” was being shared on Napster before its official release. In a historic legal move, Metallica provided the court with the usernames of 300,000 Napster users who had downloaded their music. Dr. Dre followed suit, further amplifying the industry’s case.

By July 2000, a U.S. District Judge issued an injunction that would effectively shut Napster down unless they prevented users from sharing copyrighted material. By 2001, after a series of appeals and court rulings, Napster was forced to shut its doors, filing for bankruptcy in 2002.

A Marketing Misstep: How Napster Missed the Boat

Napster’s swift demise could have been avoided, and the music industry’s war on the service might have had a different ending if both sides had recognised the growing consumer appetite for digital music access. From a marketing perspective, Napster was sitting on a gold mine of untapped potential that went far beyond piracy. The platform had already established itself as the go-to service for music enthusiasts, and its user base was massive and global.

If Napster had been able to pivot to become a legitimate marketplace for digital music, it could have played a transformative role in shaping the early digital music economy. Most reports suggest that Napster’s founders were too young, inexperienced, and blinded by the sheer growth of their platform to be able to make a deal. But it seems in hindsight that they were forced spend most of their resources on legal defence… and record companies weren’t particularly willing to make a deal – but there are two honourable mentions:

1. Bertelsmann (BMG)

The most prominent case of a record company trying to work with Napster came from Bertelsmann Music Group (BMG), one of the world’s largest record companies at the time. In October 2000, BMG made a bold move by announcing a partnership with Napster. Under this plan, BMG’s parent company, Bertelsmann AG, provided Napster with a loan to help it develop a subscription-based service that would provide legal access to music. BMG’s CEO, Thomas Middelhoff, was one of the few major industry players who saw the potential in Napster’s user base and believed that people would be willing to pay for a legitimate digital music service.

Middelhoff viewed Napster’s enormous popularity as an opportunity to create a legal digital music distribution platform that would allow record labels to profit from the growing demand for online music. His vision was that Napster could transition to a paid model where users would subscribe to legally access music.

However, this deal was met with fierce resistance from other record labels, the RIAA, and industry executives who remained focused on litigation rather than innovation. BMG’s move was seen as controversial, and although the company was willing to invest in Napster’s future, the partnership couldn’t save the service.

2. Other Industry Conversations

Beyond Bertelsmann, there were a few smaller players and individuals in the music industry who were open to discussions about working with Napster. For example, Jim Griffin, a consultant and digital media expert, encouraged music companies to work with Napster instead of fighting it. Griffin, like Middelhoff, believed that Napster represented the future of music distribution and that, rather than destroying the industry, it could be used to build a profitable digital marketplace.

However, these efforts were fragmented, and the broader industry was far more focused on legal action and protecting the traditional CD sales model. Labels like Universal, Warner, and Sony were vehemently opposed to working with Napster, as they saw it as a direct threat to their business models and were not yet prepared to embrace digital music distribution.

Why the Deals Fell Through

Ultimately, these potential deals were derailed by the ongoing lawsuits from the RIAA, which represented the collective interests of the major record labels. Napster’s reputation as a piracy haven, coupled with the industry’s legal strategy, made it nearly impossible for even open-minded companies to move forward with Napster in any meaningful way.

By the time BMG and Napster tried to make a subscription-based service a reality, the damage had already been done. The legal rulings and mounting financial pressures forced Napster to shut down in 2001, and its hopes of becoming a legitimate digital music distributor were dashed.

In hindsight, these deals could have laid the groundwork for a thriving legal digital music ecosystem years before iTunes or Spotify entered the scene. Unfortunately, the industry’s focus on litigation over innovation meant that this opportunity was missed.

Consumer Insights Napster Could Have Capitalised On

Napster users weren’t merely interested in getting free music, they were excited about the ease of access. At a time when most music was locked away on physical CDs, Napster provided instant access to an unprecedented library of songs. Users were also driven by a desire to explore new music and share tracks with friends. This cultural shift could have been the foundation for a subscription-based or à la carte digital music service.

MP3 players were becoming commonplace and in 2001 Apple launched the iPod and iTunes having agreed deals with major record companies, further supporting the argument that a deal didn’t happen with Napster due to their piracy connotations.

THAT South Park Episode – Napster vs. Metallica

In 2003, reflecting on this debacle, South Park aired the episode “Christian Rock Hard” during its seventh season, satirising the Napster and Metallica confrontation. The episode brilliantly lampooned the overblown reaction of wealthy musicians to the emerging trend of downloading music for free via platforms like Napster, which was seen by many artists, including Metallica, as a threat to their income.

In the episode, the kids form a Christian rock band as a get-rich-quick scheme, while simultaneously making fun of musicians like Lars Ulrich from Metallica, who in real life had been vocal about how Napster was robbing artists. Cartman, Stan, Kyle, and Kenny end up at a music industry seminar where they’re shown wealthy rock stars lamenting the effects of illegal downloading. Lars Ulrich is depicted as being unable to afford a gold-plated shark tank for his mansion, and Britney Spears can’t upgrade her private jet, all because of piracy.

South Park exaggerated the disconnect between wealthy musicians and the everyday music fan, poking fun at how the artists’ plight seemed out of touch. The creators highlighted the absurdity of millionaires crying over marginal losses in an age where consumers, especially young ones, were increasingly gravitating toward digital access to music. The episode reflected a common sentiment at the time: while Napster’s legality was up for debate, the way artists like Metallica responded to it made them seem greedy and unsympathetic to a new wave of tech-savvy music lovers.

The episode became a cultural touchstone, using humour to spotlight how tone-deaf the industry’s response was, while showcasing how deeply ingrained music piracy had become.

What Could Have Been: A Marketing Strategy in Hindsight

At the risk of being accused of being “Captain Hindsight” – here are a few points that could have created a sustainable model at the time.

Why didn’t I do anything at the time given my connection and career in the music industry?

The answer is that I was 15!

So take the following as you like – but I do think it’s important to learn from our mistakes!

1. A Licensing Model Instead of Litigation

Napster could have approached record companies and artists as early as 1999 to create licensing agreements. From a marketing standpoint, Napster’s 70 million users represented an untapped distribution channel, offering a faster and cheaper way to reach consumers than brick-and-mortar retailers like HMV, Virgin Records or even Tower Records. In exchange for royalties, Napster could have facilitated digital downloads of albums and singles, or even offered an early form of music streaming service. The key was to embrace a collaborative, rather than adversarial, stance with the record labels.

One crucial missed opportunity was during the rise of Apple’s iTunes in 2001. Steve Jobs recognised the demand for digital music and capitalised on the gap Napster had created by failing to legitimise its operations. Had Napster seized the opportunity earlier, it could have launched the first legal digital music store, monetising the growing digital consumer base just before Apple.

Apple showed that a deal with major record companies was there to be had – so the seemingly impossible was possible!

2. Early Adoption of a Subscription Model

In the late 1990s, subscription-based services were gaining traction in other industries (e.g., AOL for internet access). Napster could have pioneered the first music subscription model, where users paid a small monthly fee to access unlimited music. With their established base of millions of users, Napster had the infrastructure and network effect to make such a model successful. The music industry could have profited from recurring revenue, and Napster would have provided a legal and sustainable way for fans to enjoy music.

I guess that this didn’t happen because there was a lack of reconciliation between Napster and most of the record companies – but this could have been an early game changer!

3. Enhanced User Experience as a Competitive Advantage

Another key component of Napster’s success was the community it fostered. Users didn’t just download music, they discovered new artists, shared recommendations, and even interacted with each other. This social component could have been leveraged to create a more interactive digital music experience, one that allowed for personalised playlists, artist recommendations, and direct artist-to-fan interaction. Spotify, which launched in 2008, would later take advantage of this very concept. Napster, though, had the first-mover advantage and could have differentiated itself by creating deeper fan communities around artists.

One of the key reasons you discovered music so readily was because its was free, and this was 4-5 years before the launch of YouTube. The only other way at the time was to go to HMV and ask to listed to a CD on one of their CD players.

Industry’s Unpreparedness: The Blindside of Digital

One of the critical reasons the music industry waged a war against Napster was because it was blindsided by the sudden shift toward digital consumption. The record labels had built a business model that relied heavily on physical CD sales, and the infrastructure supporting that, from manufacturing to distribution to retail, had significant inertia. Napster disrupted this entire supply chain.

At the time, most industry executives either couldn’t imagine how the digital revolution could be monetised or were afraid that it would erode the profitability of CD sales. For instance, Hilary Rosen, then-CEO of the RIAA, said during the legal battles, “We support new technology, but we can’t support a business model that destroys our ability to fund the artists we represent.”

The industry missed the critical moment when it could have helped shape the digital marketplace, instead of trying to maintain the old one. Some record executives even admitted years later that their obsession with shutting down Napster delayed the industry’s move into digital. Jim Griffin, a consultant to the music industry, recalled, “The industry went to war with Napster and forgot to talk to the fans.”

The Aftermath and Lessons Learned

In retrospect, Napster’s battle with the music industry highlights how powerful shifts in technology can catch incumbents off guard. The service illuminated a demand for easy, affordable, and on-demand music, yet both Napster and the record companies were more focused on fighting each other than innovating. Napster could have built the foundation of the modern music streaming industry, while the record labels could have found new, more profitable ways to monetise music in the digital era.

Ultimately, the demand for digital music persisted, leading to the rise of platforms like iTunes, Pandora, and eventually Spotify, which now dominate the market Napster once held. While Napster’s failure is often remembered as a cautionary tale of intellectual property rights, it also serves as a reminder of the importance of adapting to technological disruption, even when it challenges established business models.

Napster might have won the future had it invested its resources in adapting to, rather than fighting, the inevitable digital revolution. It could have been remembered as the pioneer of digital music, not as a symbol of piracy. Instead, it left the door open for other companies to succeed where it failed.

The real story of Napster, then, is not just a legal drama, but a missed marketing opportunity — a “what could have been” tale of innovation, timing, and the ability to recognise the winds of change.