The Hatred of Hype

A Hilarious (but True) History of Marketing’s Most Notable Haters

Note:

This article features content from the Marketing Made Clear podcast. You can listen along to this episode on Spotify:

Marketing.

Some people, like me, see Marketing as the art of connecting people with the products, services and companies that enhance their lives. But some people see it as the art of convincing us to buy something we don’t need with money we don’t have, all while making us feel great about it.

You might also feel this way If you’ve ever been lulled into purchasing a blender or air frier you’ll never use, or a gadget that solves a problem you don’t have, but you’re not alone. The history of people disillusioned by Marketing goes way back, and some very clever folks have had a lot to say about it. From comedians to economists, from environmentalists to social critics, there’s been no shortage of individuals who have taken a very dim view of advertising and its oft-questionable role in society.

So, let’s dive into the long, entertaining history of notable haters of marketing, a tale filled with biting wit, intellectual rigor, and more eye-rolling than a teenager stuck on a family vacation.

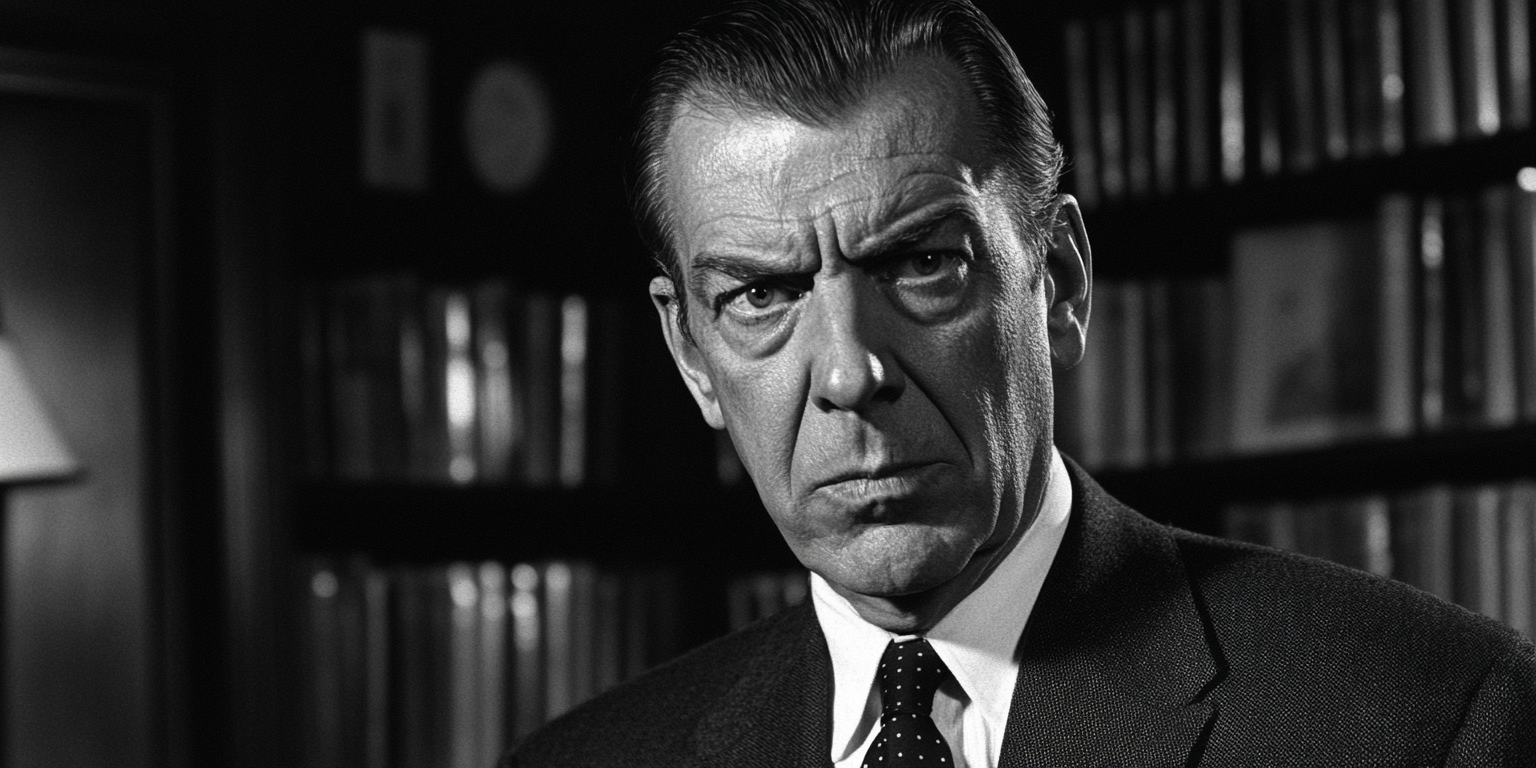

Will Rogers: The Cowboy Philosopher Who Could Smell a Sales Pitch a Mile Away

First up, Will Rogers, the O.G. of marketing mockery. Rogers was an American humorist, vaudeville performer, and, for our purposes, one of the earliest haters of the advertising industry. In the early 1900s, Rogers had some truly sharp takes on what advertisers were up to.

“If advertisers spent the same amount of money on improving their products as they do on advertising, they wouldn’t have to advertise them.”

Boom. Roasted. I’m crying at the window!

Rogers, who wielded wit like a cowboy wields a lasso, felt that he saw through the smoke and mirrors that the advertising world so expertly “peddled”. He basically invented the idea of “if your product didn’t suck, you wouldn’t need to shove it down people’s throats.” But Will wasn’t done. He followed up with another gem:

“Advertising is the art of convincing people to spend money they don’t have for something they don’t need.”

Cynical Will!

This statement has aged like a fine wine, or perhaps more fittingly, like a Black Friday sale ad.

Rogers had an uncanny ability to make the ridiculousness of consumer culture seem obvious, long before we had terms like “buyer’s remorse” or “impulse purchase regret.” He was the cowboy-poet for everyone who’s ever bought a ThighMaster and wondered, “Why?”

Vance Packard: The Hidden Persuader Who Pulled Back the Curtain

Fast-forward to 1957, and along comes sweaty Vance Packard (I don’t know why he’s sweaty sorry), wielding not a lasso of humour but a literary hammer with his book The Hidden Persuaders. If Rogers was laughing at advertisers, Packard was shaking us by the shoulders and saying, “Wake up, people! They’re playing mind games!”

Packard’s book wasn’t just a critique; it was more like a horror story. He revealed how advertisers, politicians, and fundraisers were using psychological tricks to manipulate the American public.

It was Inception before Inception was a thing.

Packard showed how we were all just puppets on strings, blissfully unaware of the subtle ways we were being nudged into buying stuff, donating to causes, or voting for candidates we’d never heard of until we saw a catchy slogan on TV.

If you’ve ever stood in the supermarket holding two brands of pasta sauce, wondering why one just “feels” like the right choice—well, blame Vance Packard for pointing out that advertisers have been messing with your head.

Sadly, Packard died in 1996 so he never got to see the depths of psychology based marketing of the 21st Century. Maybe for the best, I don’t think he would approve.

John Kenneth Galbraith: The Professor Who Called Out the Phantom Demand

A year later, in 1958, economist John Kenneth Galbraith took the baton of marketing criticism and ran with it in The Affluent Society. Galbraith wasn’t just concerned with the manipulation of the individual; he was worried about the entire society’s obsession with consumption. In his view, as America grew wealthier, private business had to artificially create consumer demand through… what else, but advertising.

According to Galbraith, we were producing and consuming so many commercial goods that we’d become blind to the neglect of the public sector. The roads, the schools, the healthcare system, who cares about those when there’s a new line of flashy cars and luxury gadgets on the market?

Galbraith’s message was clear: our obsession with stuff was turning us into a nation of empty-walleted magpies, distracted by the latest shiny objects while our infrastructure crumbled.

Galbraith essentially called out advertising for creating needs where none existed. You thought you needed that new toaster with Wi-Fi? You didn’t. You were just brainwashed.

Rachel Carson: The Naturist… Wait, No, Naturalist Who Said “Stop Buying Poison!”

In 1962, Rachel Carson, a naturalist (not to be confused with a naturist, though both are nature-related, but only one involves clothes), came out swinging against not just marketing, but marketing lies. Her book Silent Spring exposed the detrimental effects humans, and particularly big business, were having on the environment.

Carson accused the chemical industry of not only poisoning the earth but also spreading disinformation to cover their tracks. They didn’t just sell pesticides; they sold the idea that pesticides were the key to a utopian future where every garden was free of pesky bugs, and maybe, you know, plants and animals too. Carson’s issue wasn’t just with the product itself; it was with how marketing was used to make people think it was safe, even beneficial, to spray chemicals all over the place.

It turns out, dousing everything in DDT wasn’t quite the brilliant idea the commercials made it out to be. Who knew?

Rachel did.

Ralph Nader: Unsafe at Any Billboard

By 1965, Ralph Nader joined the ranks of the marketing critics, but this time, he was gunning for the auto industry. His book Unsafe at Any Speed was a scorching critique of how car manufacturers were selling us death traps on wheels. According to Nader, the cars being marketed at the time were less “vehicles of freedom” and more “death sleds with a new coat of paint.”

Car ads showed sleek, shiny cars cruising along coastal highways, but Nader exposed the terrifying truth: the auto industry was cutting corners on safety features. His work didn’t just criticize the products; it ripped apart the image that advertising was creating around them. It wasn’t just a car, they were selling you a coffin with cupholders.

Naomi Klein: “No Logo,” No Corporate Shenanigans

Skip ahead to 1999, and Naomi Klein dropped the marketing mic with No Logo. Her book was a deep dive into the ugly side of corporate branding, focusing on how companies weren’t just selling products, they were selling identities. You didn’t just buy a pair of shoes; you bought a lifestyle. And with globalization in full swing, those brands were making their profits on the backs of exploited labor and environmental degradation.

Klein’s book became the manifesto for a new generation of anti-globalisation activists, and it painted a stark picture of how corporations were manipulating culture and politics for profit. If marketing was once about selling you a product, by 1999 it was selling you you—or at least, the “you” the corporations wanted you to think you should be.

Michael Sandel: Putting a Price Tag on Everything? Not So Fast

Finally, in 2012, Michael Sandel entered the chat with What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets. Sandel wasn’t just concerned with advertising’s ability to sell products; he was questioning whether there were some things that shouldn’t be sold at all. Should we be able to buy and sell moral values, human rights, or access to basic needs?

Sandel’s book takes the debate beyond the usual marketing critique. He wasn’t just saying “advertising is manipulative.” He was asking whether it’s ethical for market forces to dictate the terms of human interaction and values. In a world where everything seems to have a price tag, Sandel was that voice in the back of your head whispering, “Hey, should it?”

Conclusion: The Haters Gonna Hate, but Maybe They’re Right?

From Will Rogers’ hilarious quips to Michael Sandel’s deep moral questions, the critics of marketing have always had something important to say. Whether they’re cracking jokes or writing serious critiques, they all agree on one thing: marketing, in its purest form, is designed to make us want what we don’t need. And while there’s certainly an art to that, it’s not always a noble one.

So the next time you see a commercial for something you don’t need, remember: there’s a long history of very smart, very funny, and very outraged people who have been telling you not to buy it.